Concrete structures are the backbone of modern infrastructure, supporting everything from buildings and bridges to nuclear power plants. Over time, these structures are subjected to various environmental and operational stresses that can lead to degradation. Assessing the condition of existing concrete structures is essential to ensure their safety, functionality, and longevity.

This blog post will explore the essentials of assessments of the condition of existing concrete structures, concrete degradation mechanisms, investigation methods, and equipment used for evaluation. We will also discuss the advantages and limitations of these assessment methods.

Why Assess the Condition of Concrete Structures?

Assessing the condition of existing concrete structures is crucial for several reasons:

- Safety: Ensuring the structural integrity of concrete structures is paramount to prevent failures that could lead to accidents and loss of life.

- Maintenance: Regular assessments help identify potential issues early, allowing for timely maintenance and repairs to extend the structure’s lifespan.

- Cost Efficiency: Early detection of problems can prevent minor issues from becoming major, costly repairs.

- Regulatory Compliance: Many industries, especially nuclear power and civil engineering, have strict regulations requiring regular inspections and assessments.

- Risk Management: Understanding the current state of a structure helps in managing risks associated with its continued use.

Types of Structures That Need Assessment

Several types of concrete structures require regular condition assessments:

- Nuclear Power Plants: Reactor containment structures and cooling water systems are critical components that must be regularly inspected due to their safety implications.

- Bridges and Tunnels: These structures are exposed to various environmental factors and heavy loads, making them susceptible to degradation.

- Buildings: High-rise buildings, especially those in urban environments, need regular assessments to ensure structural integrity.

- Dams and Water Retention Structures: These structures are critical for water management and flood control, requiring regular inspection to prevent catastrophic failures.

- Industrial Facilities: Factories and warehouses often have concrete structures subjected to harsh industrial environments and heavy machinery.

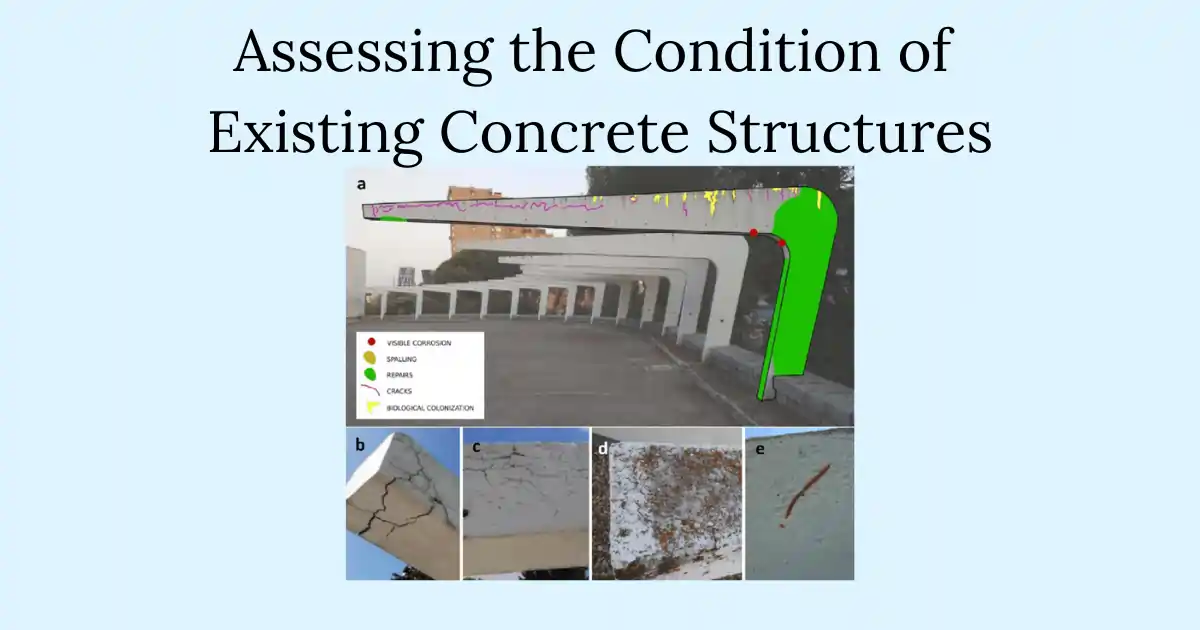

Symptoms of Concrete Degradation

Concrete degradation can manifest in various forms, each with its own causes:

- Corrosion: The primary cause is the ingress of chloride ions or carbonation, leading to the breakdown of the protective oxide layer on reinforcing steel.

- Cracking: Can be caused by thermal stresses, shrinkage, or external loads.

- Erosion: Occurs due to the abrasive action of water or wind, especially in structures exposed to flowing water.

- Spalling: The breaking off of surface layers, often due to freeze-thaw cycles or chemical attacks.

- Efflorescence: White deposits on the surface caused by the leaching of soluble salts.

- Alkali-Silica Reaction (ASR): A chemical reaction between alkalis in cement and reactive silica in aggregates, leading to expansion and cracking.

- Sulfate Attack: Caused by the ingress of sulfate ions, leading to the formation of expansive products that degrade the concrete.

- Freeze-thaw damage: Repeated cycles of freezing and thawing can cause the concrete to crack and deteriorate.

- Biomass Accumulation: Biological growth on the surface, which can lead to further degradation.

Degradation Mechanisms in Concrete

Concrete, like any other material, is susceptible to degradation over time. Understanding the various degradation mechanisms is crucial for assessing the condition of existing concrete structures. These mechanisms can be broadly categorized into physical, chemical, and environmental factors.

Physical Degradation Mechanisms

- Freeze-Thaw Cycles:

- Mechanism: When water freezes, it expands by approximately 9%, exerting significant pressure within the concrete. Repeated cycles of freezing and thawing can cause microcracks to form and propagate, leading to surface scaling and spalling.

- Symptoms: Surface scaling, spalling, and the formation of visible cracks.

- Mitigation: Using air-entrained concrete, which contains tiny air bubbles that act as expansion chambers, can reduce the risk of freeze-thaw damage.

- Thermal Expansion and Contraction:

- Mechanism: Concrete expands when heated and contracts when cooled. This can lead to thermal stresses, especially in structures subjected to significant temperature variations.

- Symptoms: Cracking along joints, delamination, and surface distress.

- Mitigation: Properly designed expansion and contraction joints can help manage thermal stresses.

- Erosion:

- Mechanism: Erosion occurs when flowing water or abrasive particles wear away the surface of the concrete. This is particularly common in structures such as dams, spillways, and cooling water systems.

- Symptoms: Surface wear, loss of aggregate, and exposure of reinforcement.

- Mitigation: Using high-strength, erosion-resistant concrete and protective coatings can mitigate erosion.

Chemical Degradation Mechanisms

- Carbonation:

- Mechanism: Carbonation is the reaction of carbon dioxide in the air with calcium hydroxide in the concrete, forming calcium carbonate. Normally, the alkaline environment of concrete, of about pH 12-13, promotes the creation of a stable oxide layer called passive film.

- The carbonation reaction reduces the alkalinity of the concrete; an alkalinity of less than pH 9-11 can lead to the depassivation of the reinforcing steel and initiate corrosion in the presence of moisture and oxygen.

- Symptoms: Surface discoloration, increased porosity, and potential corrosion of reinforcement.

- Mitigation: Using low-permeability concrete and applying protective coatings can slow down the carbonation process.

- Chloride Attack:

- Mechanism: It is estimated that 40% of concrete structures fail from chloride attack. Chloride ions from sea water, deicing salts, and other sources can penetrate the concrete and react with the reinforcing steel, breaking down the passive oxide layer and causing corrosion.

- Symptoms: Rust stains on the surface, cracking, and spalling.

- Mitigation: Using chloride-resistant admixtures, low-permeability concrete, and cathodic protection systems can help mitigate chloride attack.

- Alkali-Silica Reaction (ASR):

- Mechanism: ASR occurs when alkalis in the cement react with reactive silica in the aggregates, forming an expansive gel that can cause cracking and expansion.

- Symptoms: Map cracking (a pattern resembling a map), surface bulging, and potential structural distress.

- Mitigation: Using low-alkali cement, non-reactive aggregates, and lithium-based admixtures can help prevent ASR.

ASR ASR concrete pillar, Courtesy of photos Wikimedia

- Sulfate Attack:

- Mechanism: Sulfates in the environment, such as ground water, sea water, and soil can react with the concrete’s constituents, such as calcium hydroxide and aluminium hydrate. The reaction results in the formation of expansive products, such as ettringite and gypsum, which can cause cracking and degradation.

- Symptoms: Cracking, surface scaling, and loss of strength.

- Mitigation: Using sulfate-resistant cement and low-permeability concrete can help mitigate sulfate attack.

Environmental Degradation Mechanisms

- Biological Growth:

- Mechanism: Biological growth, such as algae, moss, and lichen, can occur on the surface of concrete, especially in damp environments. This can lead to surface discoloration and potential degradation.

- Symptoms: Surface discoloration, staining, and potential surface weakening.

- Mitigation: Regular cleaning and the use of anti-biological coatings can help control biological growth.

Biological deterioration of concrete, Courtesy of photos amphoraconsulting.co.uk/

- Radiation Exposure:

- Mechanism: In nuclear power plants, concrete structures are exposed to radiation, which can cause changes in the concrete’s microstructure, leading to degradation.

- Symptoms: Changes in mechanical properties, increased porosity, and potential cracking.

- Mitigation: Using high-quality, radiation-resistant concrete and regular inspections can help manage radiation-induced degradation.

Methods for Concrete Assessment

Several methods are used to assess the condition of concrete structures:

- Visual Inspection: The simplest method, involving a visual examination of the structure for signs of degradation.

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): Techniques that do not damage the structure,

The following are some of the non-destructive testing methods (NDT) of investigation used in the assessment of existing concrete structures.

- Ultrasonic Testing: Uses high-frequency sound waves to detect internal defects.

- Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR): Uses radar pulses to image the subsurface, detecting reinforcing bars, voids, and cracks.

- Electrical Resistivity: Measures the electrical resistance of concrete to assess its moisture content and potential for corrosion.

- Half-Cell Potential: Measures the potential difference between the reinforcing steel and a reference electrode to assess the risk of corrosion.

- Destructive Testing: Involves taking samples for laboratory analysis, such as:

- Core Sampling: Extracting cylindrical samples for compressive strength testing.

- Chemical Analysis: Testing for chloride and sulfate content.

- Structural Monitoring: Continuous monitoring using sensors to detect changes over time.

Equipment and Tests for Concrete Assessment

Various tools and tests are used in concrete assessment:

- Ultrasonic Equipment: Used for ultrasonic testing to detect internal defects.

- GPR Systems: For ground penetrating radar to image the subsurface.

- Corrosion Meters: To measure electrical resistivity and half-cell potential.

- Core Drills: For extracting core samples for laboratory analysis.

- Chemical Analysis Kits: For testing chloride and sulfate content.

- Visual Inspection Tools: Such as cameras and drones for hard-to-reach areas.

- Thermographic Cameras: To detect temperature variations indicating moisture or delamination.

Advantages and Limitations of Assessment Methods

Each assessment method has its advantages and limitations:

- Visual Inspection:

- Advantages: Simple, quick, and cost-effective.

- Limitations: Limited to surface defects and requires experienced inspectors.

- Ultrasonic Testing:

- Advantages: Can detect internal defects without damaging the structure.

- Limitations: Requires skilled operators and can be time-consuming.

- Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR):

- Advantages: Non-destructive and can cover large areas quickly.

- Limitations: Interpretation of results requires expertise and can be affected by environmental conditions.

- Electrical Resistivity:

- Advantages: Non-destructive and provides information on moisture content.

- Limitations: Limited to surface measurements and requires calibration.

- Half-Cell Potential:

- Advantages: Non-destructive and provides information on corrosion risk.

- Limitations: Limited to structures with accessible reinforcement and affected by moisture content.

- Core Sampling:

- Advantages: Provides accurate information on strength and composition.

- Limitations: Destructive and requires laboratory analysis.

- Chemical Analysis:

- Advantages: Provides detailed information on chloride and sulfate content.

- Limitations: Destructive and requires laboratory analysis.

Assessing the condition of existing concrete structures is a critical task that ensures safety, functionality, and longevity. Understanding the symptoms of concrete degradation and the methods available for assessment is essential for effective maintenance and management.

While each method has its advantages and limitations, a combination of visual inspection, non-destructive testing, and selective destructive testing often provides the most comprehensive assessment. Regular condition assessments are a regulatory requirement and a best practice for any infrastructure manager. By staying vigilant and proactive, we can ensure that our concrete structures remain safe and functional for generations to come.

Sources:

Oförstörande provning, OFP, av betongkonstruktioner

201810-tillstandsbedomningar-av-betongstrukturer-inom-karnkraft—bekon

Carbonation of Reinforced Concrete – Ronacrete