The arch stands as one of humanity’s most significant architectural innovations, revolutionizing the way we span distances and support structures. Its use dates back approximately 4,000 years back to ancient Mesopotamia.. Its unique structural property sets it apart from simpler support systems that rely on vertical force distribution, in that arches employ the geometry to redirect weight into compression.This structural characteristics has allowed architects and engineers to create larger, more durable, and aesthetically striking structures.

The Historical Evolution of Arches

Ancient Origins and Roman Mastery

The earliest evidence of arches dates to around 2000 BCE in Mesopotamia, where ancient Sumerians and Babylonians constructed brick arches for underground drainage systems. The Egyptians later developed crude corbel arches—sometimes called “false arches”—for tombs and underground structures around the 4th millennium BC, though few examples survive today.

However, it was the Romans who fundamentally transformed arch technology. While the Romans likely adopted the arch concept from the Etruscans around the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, they perfected and popularized its use in monumental architecture. Beginning in the first century BCE, Roman engineers applied arches extensively to aqueducts, amphitheaters, bridges, and public buildings, creating structures that would endure for over two millennia. The semicircular arch became synonymous with Roman architecture and engineering excellence.

Islamic Influence and Geometric Innovation

Following Rome’s decline, Islamic architecture became the next great innovator of arch design. Islamic architects introduced sophisticated variations of the arch, including the four-centered arch (which first appeared in 9th-century Samarra), pointed arches, horseshoe arches, and elaborate multifoil arches. The Great Mosque of Córdoba, built over centuries starting in 785, exemplifies how Islamic architects refined and elaborated arches with intersecting cusped and polylobed designs that served both structural and decorative purposes.wikipedia+2

Medieval European Development

The pointed archAlso known as a two-centred arch,, which may have distant Byzantine origins but gained particular prominence through Islamic influence, revolutionized medieval European architecture beginning in the 11th century. This innovation allowed Gothic architects to create cathedrals of unprecedented height and interior light. By the 12th century, the pointed arch had become an essential element of Gothic architecture in France and England, working in concert with other innovations like rib vaults and flying buttresses to create structures that soared dramatically upward.

Understanding the Mechanics: How Arches Work

Compression vs. Tension

The fundamental advantage of arches lies in how they handle structural forces. Unlike lintels or beams—which work through bending and depend on tensile stresses for strength —arches function primarily through compression.

When a load is applied to an arch, the structure redirects this vertical load along its curved path, transforming it into compressive forces that travel outward and downward toward the supports at either end (called abutments or piers).

In an ideal arch design, tension is negligible, and the structure relies entirely on the ability of its materials to resist compression—something that stone, concrete, and brick do exceptionally well.

This fundamental difference explains why arches can span larger distances than flat lintels of comparable dimensions and why they can support greater loads without requiring massive thickness.

Force Distribution and Load Path

In a properly designed arch, forces follow a predictable path called the “line of thrust.” This imaginary line traces the path of compressive stress through the arch structure. When forces remain within the middle third of the arch’s thickness, stresses distribute evenly across the entire cross-section. If forces move outside this region, uneven stress distribution occurs, potentially causing cracking in the mortar joints.

The effectiveness of an arch depends critically on adequate abutment support. Unlike lintels, which only generate vertical loads directly downward, arches generate significant lateral thrust at their bases—a horizontal force pushing outward against the supporting structures. This thrust must be contained by robust abutments or piers; if they’re insufficient, the arch will collapse as the supports are forced apart.

Voussoirs and Keystones

Arches are constructed from carefully shaped wedge-like stones or bricks called voussoirs. Each voussoir is positioned so that it intersects with its neighbors at angles that direct thrust outward and downward through the arch structure. The springer voussoirs at each side form the beginning of the arch, while the keystone—the central wedge placed at the arch’s apex—locks all components together.

The keystone’s importance transcends mere mechanics; it serves as both the physical lock that prevents voussoirs from slipping outward and a symbolic element highlighted by decorative carving throughout architectural history. When the keystone is properly set, the self-supporting nature of the arch becomes apparent: each voussoir presses against its neighbors, creating a locked structure that becomes stronger under load.

Classification and Types of Arches

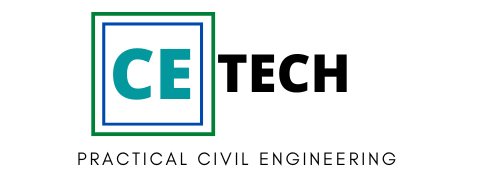

Arches are classified using multiple criteria: shape (based on the curve of the intrados—the inner surface), the number of centers used in their geometric construction, materials employed, and architectural style.

One-Centered Arches (Circular Arches)

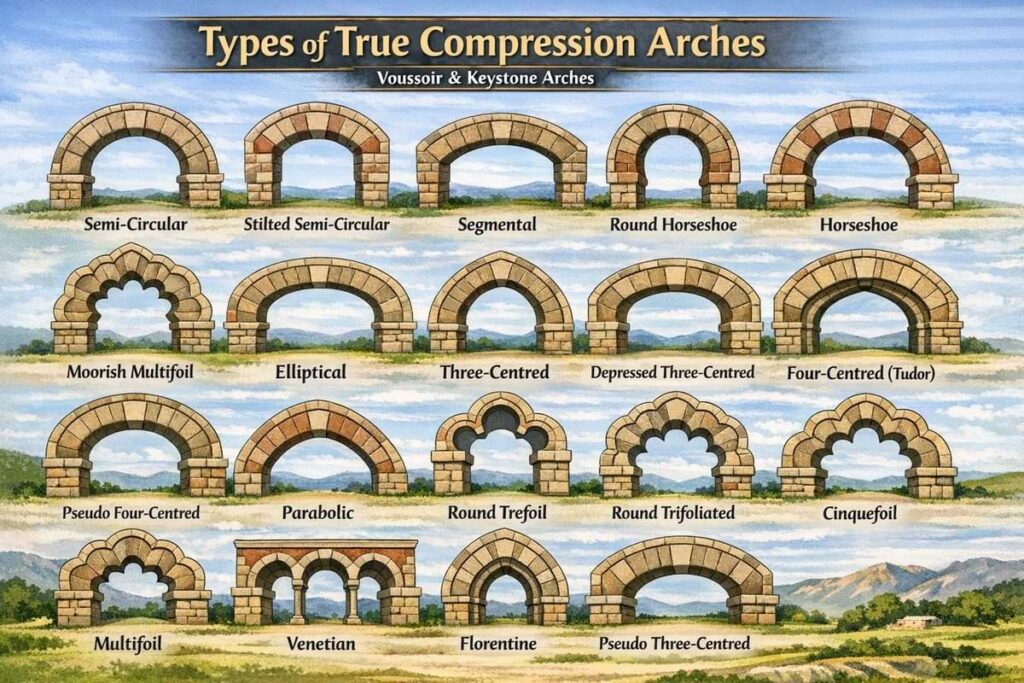

Semicircular (Roman) Arch

The most basic and widely used arch type, the semicircular arch. It forms a perfect half-circle with a rise (height) equal to exactly half its span (the distance between supports). This elegant simplicity made it the preferred choice of Roman engineers for aqueducts, bridges, and amphitheaters. The Colosseum employs 80 semicircular entrance arches arranged in three tiers, each decorated with engaged columns of different classical orders.

Advantages: The semicircular arch’s simple geometry makes layout and construction straightforward. Its predictable behavior under load and proven durability across centuries make it ideal for permanent structures.

Disadvantages: The semicircular arch swings wider than the ideal funicular curve (the theoretical perfect shape for a given load), creating bending moments that push outward. This requires heavy spandrel fill or abutment walls to contain lateral thrust.(The ideal funicular curve is parabola that results in zero moment and pure axial forces reducing the size of sections)

Segmental Arch

This arch forms less than a semicircle, with a rise significantly less than half its span. Segmental arches are used when height is limited or when aesthetic considerations favor a flatter appearance. The thrust transfers to abutments at an incline rather than vertically.

Advantages: Maximizes headroom in constrained vertical spaces while maintaining significant load-bearing capacity.

Disadvantages: Requires more substantial abutments to handle the more horizontal thrust direction.

Horseshoe Arch

The horseshoe arch curves more than a semicircle, extending below the springing line (where the curve begins). This distinctive shape, strongly associated with Islamic and Moorish architecture, provides greater height while maintaining a given span. Examples appear throughout the Alhambra and Al-Andalus structures in Spain and North Africa.

Advantages: Creates dramatic vertical height; becomes visually prominent and distinctive.

Technical note: Can be thought of as a stilted variant—a semicircular arch with the masonry below the springing line extending inward.

Stilted Arch

A stilted arch combines vertical sections (the “stilts”) at the base with a curved upper portion. Both semicircular and pointed arches can be stilted. This design was frequently employed in Byzantine and Islamic architecture when arches needed to appear taller without increasing actual rise, or when spacing required unequal arch widths that nonetheless needed to reach the same height.

Two-Centered Arches (Pointed Arches)

Pointed (Gothic/Ogival) Arch

The pointed arch, formed by the intersection of two circular arcs that meet at the apex, fundamentally changed medieval architecture. While pointed arches existed in ancient times at Bronze-Age Nippur and later in Byzantine and Sassanian architecture, they became a defining feature of Gothic architecture beginning in the 12th century.

These arches were central to Gothic innovation: by directing thrust more steeply downward rather than outward, pointed arches created less lateral stress on supporting walls and allowed builders to construct taller buildings with thinner walls and larger windows

The Equilateral Arch Variant: The most common Gothic pointed arch was based on an equilateral triangle, where the three sides have equal length and the span equals the arc radii. This geometric simplicity allowed stone cutters to precisely prepare voussoirs at quarries for assembly at the construction site.

Theological Significance: The three-sided geometry was given spiritual meaning—the three sides represented the Holy Trinity, a symbolic interpretation that infused medieval sacred geometry.

Advantages: Allows exceptionally tall structures relative to span; reduces lateral thrust, minimizing required wall thickness; permits larger window and opening sizes; adjustable proportions work for varying widths while maintaining equal heights.

Real Examples: Notre-Dame de Paris employs pointed arches throughout its magnificent 127-meter length and 48-meter width, with pointed arches in its towering 33-meter-high nave that create the soaring verticality characteristic of Gothic design.

Lancet Arch

A sharply pointed Gothic arch with two centers and radii significantly larger than the span, the lancet arch appears narrow and spear-like. These arches became characteristic of Early Gothic architecture (exemplified by Saint-Denis Abbey in France) and achieved particular prominence in English cathedrals like Salisbury Cathedral during the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

Drop Arch

A variant of the lancet arch where the centers of the two arcs are located within the span rather than outside, creating a blunter, less pointed appearance. Drop arches appeared frequently in later Gothic architecture.

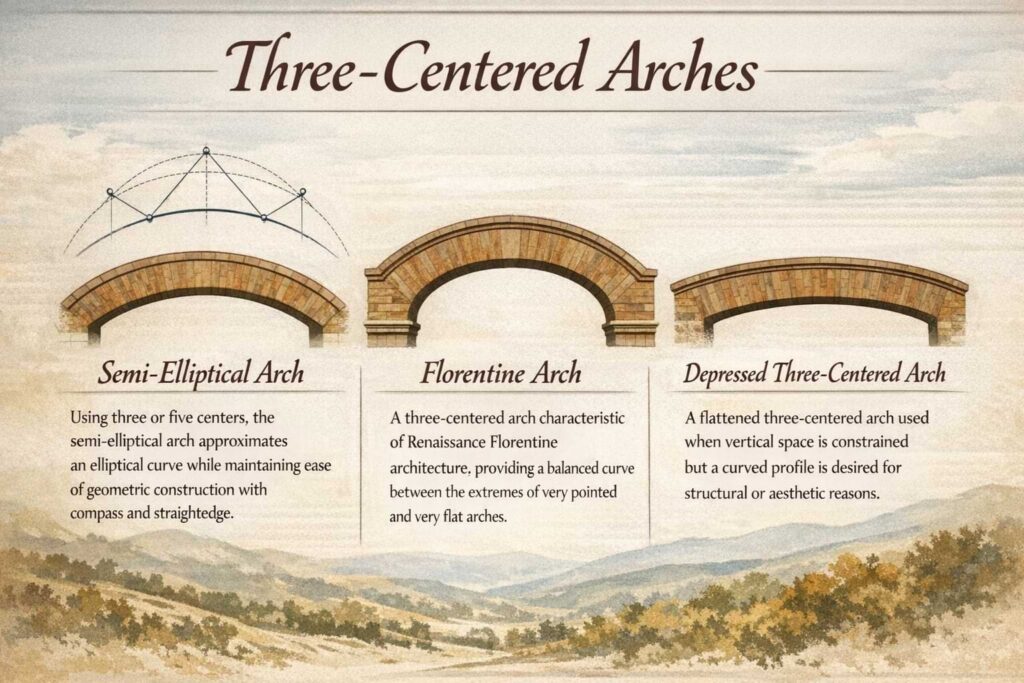

Three-Centered Arches

Semi-Elliptical Arch

Using three or five centers, the semi-elliptical arch approximates an elliptical curve while maintaining ease of geometric construction with compass and straightedge.

Florentine Arch

A three-centered arch characteristic of Renaissance Florentine architecture, providing a balanced curve between the extremes of very pointed and very flat arches.

Depressed Three-Centered Arch

A flattened three-centered arch used when vertical space is constrained but a curved profile is desired for structural or aesthetic reasons.

Four-Centered Arches

Four-Centered Arch

This distinctive arch combines four circular arcs to create a low, wide profile with a pointed apex. The structure features two steep inner arcs rising from each springing point on a small radius, then transitions to two outer arcs with much wider radius and lower apex.

The four-centered arch emerged in Islamic architecture, first appearing at 9th-century Samarra in structures like the Qubbat al-Sulaiybiyya and Qasr al-‘Ashiq. It later became standard in Persianate, Timurid, and Mughal architecture, appearing in arcades, windows, gateways, and iwans throughout Iran and Central Asia.

In English architecture, the four-centered arch became known as the Tudor arch, used extensively during the Tudor period (1485–1603), though technically the Tudor arch has two straight sides rather than the large shallow curves of a true four-centered arch. The Tudor arch provided ideal proportions for wide doorways and windows without excessive overhead height, as demonstrated at Hampton Court Palace and in the Perpendicular Gothic masterpieces like King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, where the magnificent fan vault ceiling (the largest in the world) rests above Tudor arches.

Persian Arch: A moderately depressed variant commonly found in Islamic architecture.

Keel Arch: A variant with partially straight rather than curved sides, developed in Fatimid architecture.

Advantages: Exceptionally space-efficient for wide openings; decorative possibilities; horizontal thrust manageable with proper design.

Funicular arches

Parabolic Arch

The parabolic arch uses a mathematical parabolic curve rather than a circular arc. These arches are theoretically optimal when loads are uniformly distributed and the arch’s own weight is negligible. They are optimised for uniform line load as compared to catenary arches that are optimised for uniform self-dead weight.

Advantages: Produces the most thrust at the base but can span the largest areas; ideal for bridge design requiring long spans.

Catenary Arch

Related to parabolic arches, the catenary represents the ideal shape for an arch of uniform thickness carrying only its own weight. Named for the curve formed by a hanging chain, the catenary was famously employed by Antoni Gaudí in structures like the Palau Güell.

Other Non Circular arches

Elliptical Arch

An elliptical arch follows an elliptical curve (or an approximation created by three or five circular arcs). The Ponte Santa Trinita in Florence, constructed from 1567 to 1569 by Bartolomeo Ammannati, exemplifies Renaissance elegance with its flattened elliptical arches spanning the Arno River.

Advantages: Provides distinctive aesthetic appeal while distributing loads smoothly.

Flat Arch (Jack Arch)

Unlike true arches, flat arches are essentially straight across, yet function as genuine arches rather than lintels. They use irregular voussoir shapes—wedges that compensate for the horizontal profile—to create compression-based load transfer. Flat arches require wedge-shaped keystones and significant lateral support, but they maximize usable headroom.

Corbelled (False) Arch

The corbelled arch uses the corbeling technique: successive courses of horizontal stone or brick are offset to project progressively inward from each side until they meet at the center. This creates an arch-like appearance, but it’s not a true arch because it doesn’t rely on mutually supporting voussoirs. Rather, each stone essentially cantilevers from the one below. Corbelling was employed by ancient Egyptians and Chaldeans, and appears in Celtic passage tombs like Newgrange (built 3200-2500 BC).

Advantages: Requires less skilled labor; avoids need for centering (temporary support) during construction.

Disadvantages: Less efficient than true arches; requires thickened walls and substantial abutments to resist the cantilevered forces.

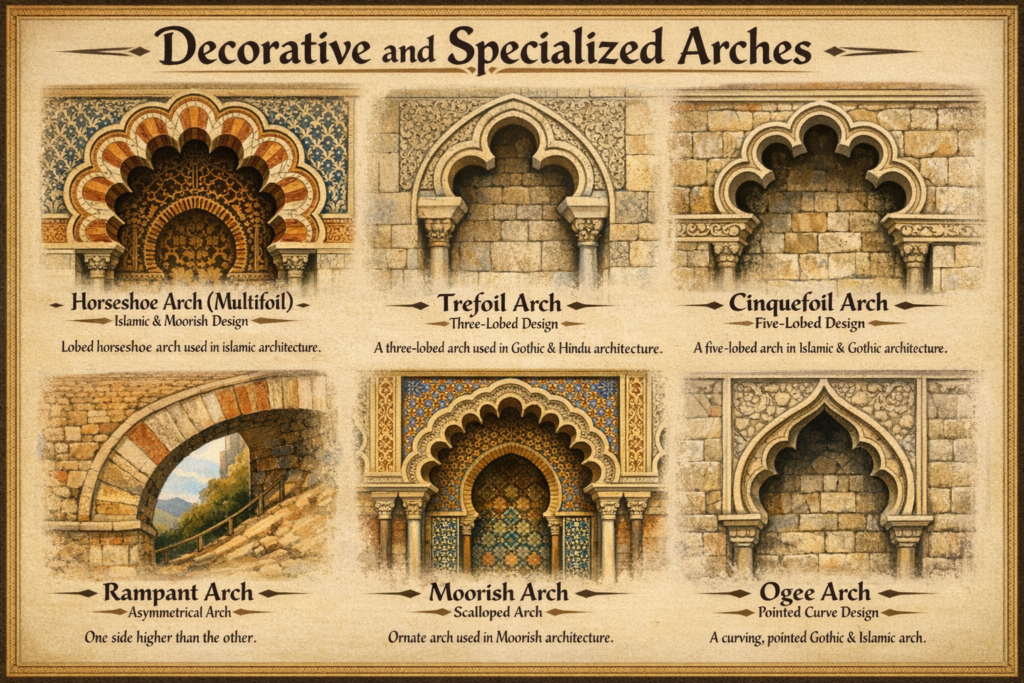

Decorative and Specialized Arches

Horseshoe Arch (Multifoil)

A specialized horseshoe arch incorporating multiple lobes (three for trefoil, four for quatrefoil, five for cinquefoil, etc.). These distinctive shapes are characteristic of Islamic, Moorish, and later Gothic decorative architectural work.

Origins and Spread: Multifoil arches were first developed by the Umayyads and appear in 9th-century structures like the Great Mosque of Cordoba, where they served both structural and decorative functions. The form spread throughout Islamic architecture in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, later influencing Gothic architecture where trefoil and cinquefoil arches became common decorative elements for portals and tracery.

Trefoil Arch: A three-lobed arch appearing in Hindu temple architecture in Kashmir from the 8th century onward, and later in Islamic and Gothic architecture for decorative purposes.

Cinquefoil and Multifoil Arches: Five-lobed and multi-lobed variations that became prominent in Fatimid, Mamluk, and later Gothic architecture, often serving as decorative niches or tracery elements.

Rampant Arch

An asymmetrical arch where one side rises higher than the other, sometimes employed when adapting arches to sloping ground or architectural constraints.

Moorish Arch

A decorative arch style with scalloped or lobed inner edge, characteristic of Moorish architecture in Spain and North Africa.

Ogee Arch

An arch with a concave and convex curve creating a pointed shape with inward-curving sides, common in late Gothic and Islamic architecture.

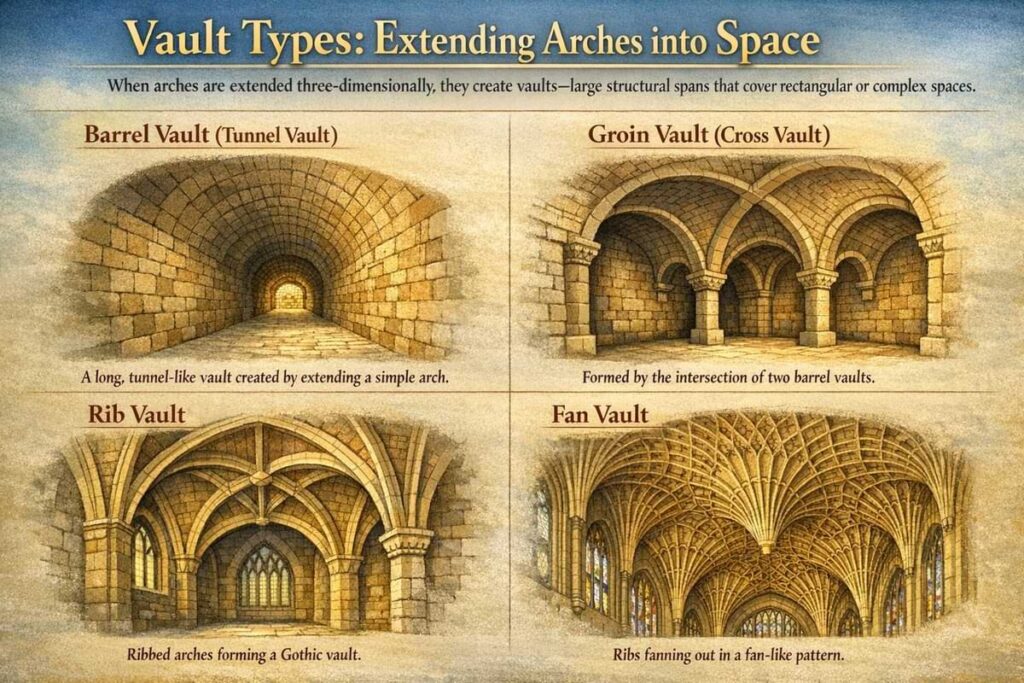

Vault Types: Extending Arches into Space

When arches are extended three-dimensionally, they create vaults—large structural spans that cover rectangular or complex spaces.

Barrel Vault (Tunnel Vault)

A continuous semicircular arch extended linearly, creating a tunnel-like structure. These vaults span long corridors or naves efficiently but concentrate stress along the length of supporting walls.

Groin Vault (Cross Vault)

Formed by the perpendicular intersection of two barrel vaults, groin vaults create a more structurally efficient design. The intersecting ridges (groins) direct stress to four corner supports rather than along entire walls, allowing thinner walls and larger window openings. The Colosseum pioneered groin vaults in the corridors beneath the arena seats.

Rib Vault

Ribs are arched structural members that meet at the vault surface, dividing the vault into geometric panels supported by the ribs rather than the vault surface itself. This innovation, central to Gothic architecture, allows lighter vault construction and creates striking visual patterns. King’s College Chapel features the world’s largest fan vault—a specialized rib vault with ribs spreading like a fan from each corner.

Fan Vault

A rib vault where ribs spread outward from each corner like a fan’s ribs. Fan vaults feature concave sections between ribs and create extraordinary visual drama. This English innovation appears at its finest in King’s College Chapel, where Henry VII’s glorious fan vault ceiling (constructed 1512-1515 under the direction of master mason John Wastell) creates one of architecture’s supreme achievements.

Here’s a parallel blog-style section for Domes, written to match the tone, depth, and structure of your vaults section:

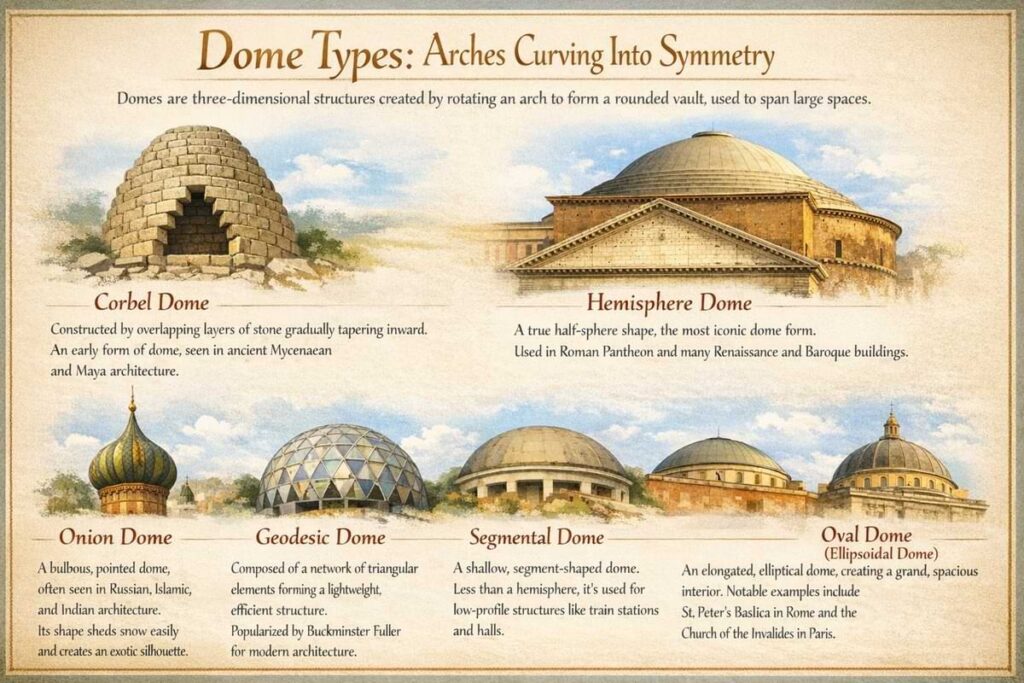

Dome Types: Extending Arches into Spheres

When an arch is rotated around its vertical axis, it forms a dome—a three-dimensional curved structure capable of spanning large circular or polygonal spaces with remarkable efficiency and beauty.

Hemispherical Dome

A classic dome shaped like half a sphere.

Derived from the geometry of a perfect arch, the hemispherical dome distributes weight evenly in all directions. This form was mastered by the Romans, whose use of concrete allowed unprecedented scale. The Pantheon remains the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome, demonstrating the incredible stability achieved through thick supporting walls and carefully graded aggregate in the concrete.

Corbel Dome

Built by stacking progressively smaller horizontal rings of stone or brick that gradually meet at the top, rather than using a true curved surface.

Corbel domes rely on cantilevered construction instead of compression along a continuous curve. They appear in ancient cultures worldwide—from the beehive-like Treasury of Atreus in Mycenae to traditional Middle Eastern architecture—showcasing early solutions for spanning circular spaces before true arches were developed.

Onion Dome

Recognizable for its bulbous, flaring profile that widens before tapering to a point.

Onion domes are structurally similar to hemispherical or pointed domes but feature an elongated silhouette adapted to cold climates where steep curvature helps shed snow. They are iconic in Russian and South Asian architecture, famously crowning St. Basil’s Cathedral with their brilliantly colored, swirling forms.

Pointed (Gothic) Dome

A dome formed from pointed or ogival arches rotated around a vertical axis.

The pointed profile reduces horizontal thrust, allowing for taller, slimmer supporting structures compared to hemispherical domes. These domes appear in Islamic and Gothic traditions—the Dome of the Rock provides a celebrated early example—highlighting how geometry can lighten load while dramatically altering aesthetic effect.

Geodesic Dome

A modern dome composed of interlocking triangular elements arranged in a spherical or partial-spherical framework.

Pioneered by Buckminster Fuller, the geodesic dome achieves high strength with minimal material by distributing forces along a network of triangles. Its lightweight, modular design makes it extremely efficient and resistant to wind loads. Today, geodesic domes appear in everything from exhibition halls to eco-living structures.

Advantages of Arch Construction

The persistence of arch design across 4,000 years of human civilization reflects profound structural and practical advantages:

Structural Efficiency

Arches distribute weight through compression, a force that stone, brick, and concrete resist superbly. This allows arches to span larger distances than lintels of equivalent material and dimensions.

The compression-based design means that arches become stronger under load—each voussoir presses tighter against its neighbors as weight increases, creating self-locking behavior absent in lintel systems. Beams, by contrast, become progressively more flexible with increased length: doubling a beam’s length makes it 16 times more flexible, leading to sagging and potential failure.

Material Efficiency

Arches require no tension-resistant steel reinforcement (crucial in masonry arches) because forces remain entirely compressive. This allowed medieval builders to create extraordinary structures using only stone, mortar, and geometry.

Durability and Permanence

Stone and concrete arch structures can endure for centuries or millennia with minimal maintenance. The Roman aqueducts—including the Pont du Gard (built 40 AD), Aqueduct of Segovia (built circa 50 AD), and the Claudio Aqueduct (completed 52 AD)—continue functioning after nearly 2,000 years, testament to compression-based design’s durability. The Pont du Gard’s four-tiered arches originally carried fresh water 50 kilometers to supply Nîmes, a city that had grown to 20,000 inhabitants.

Architectural Flexibility

Arches enable construction of vaults and domes, creating varied interior spaces and dramatic aesthetic effects impossible with lintels. The Gothic achievement—soaring cathedrals with pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses—would have been literally impossible using post-and-lintel construction.

Disadvantages and Limitations

Understanding arch limitations explains why lintels remain prevalent in modern construction:

Space Requirements

Arches require substantial rise (height) into the opening space, reducing usable headroom compared to flat lintels spanning the same distance. A semicircular arch requires rise equal to half its span; obtaining greater headroom requires widening the opening, stilting the arch, or employing a flatter form like a segmental arch with compromised structural efficiency.

Abutment Demands

The lateral thrust of arches demands robust abutments—thickened walls, buttresses, or external bracing—to contain outward forces. Lintels generate only downward force, requiring simpler support. In tight urban spaces where thickened walls are impractical, lintels prove preferable.

Construction Complexity

Building traditional arches requires centering (temporary formwork precisely shaped to the arch curve) to support voussoirs during construction while mortar sets. Properly executed, this is labor-intensive and requires skilled masons. Lintels—particularly modern precast concrete or steel beams—require only simple rectangular formwork or can be lifted directly into place. This explains why lintels dominate modern construction: faster, cheaper, less skilled labor required.

Conclusion

The arch represents one of humanity’s most enduring structural innovations. The evolution of arch design across cultures—from ancient Mesopotamia through Islamic Golden Age to European Gothic—demonstrates how structural necessity and artistic ambition intertwine. Each innovation (pointed arches allowing greater height, four-centered arches enabling wider openings,funicular arches realising economic designs, fan vaults creating visual spectacle) solved real engineering problems while advancing architectural expression.